In a recent interview with The Ordinariate Observer, Monsignor Jeffrey Steenson, the Ordinary of the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter, was asked about Divine Worship: The Missal and its relationship to the Anglican patrimony. His response was instructive, and is perhaps a useful means of understanding how the communities of the personal ordinariates will receive anew those traditions and practices which sustained their life within Anglicanism, and which have prompted within them aspirations to full communion with the Catholic Church. He said: “Anglican patrimony can be defined by as many people that happen to be in a room at that time. The Holy See helped us to define what is genuinely Catholic in these Anglican texts. Left to our own devices, we could not have defined our patrimony, simply because it is too various and too diverse; every congregation has a definition of ‘what is’ the distinctive Anglican patrimony of those they represent. Anglican patrimony was principally expressed locally, not universally. The Holy See needed to come in and help us ‘see it.’”

In a recent interview with The Ordinariate Observer, Monsignor Jeffrey Steenson, the Ordinary of the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter, was asked about Divine Worship: The Missal and its relationship to the Anglican patrimony. His response was instructive, and is perhaps a useful means of understanding how the communities of the personal ordinariates will receive anew those traditions and practices which sustained their life within Anglicanism, and which have prompted within them aspirations to full communion with the Catholic Church. He said: “Anglican patrimony can be defined by as many people that happen to be in a room at that time. The Holy See helped us to define what is genuinely Catholic in these Anglican texts. Left to our own devices, we could not have defined our patrimony, simply because it is too various and too diverse; every congregation has a definition of ‘what is’ the distinctive Anglican patrimony of those they represent. Anglican patrimony was principally expressed locally, not universally. The Holy See needed to come in and help us ‘see it.’”

This is an important hermeneutical principle with regard to the personal ordinariates in general, and the implementation of the proper liturgical texts approved by the Apostolic See in particular. A temptation seemingly exists, both within and without the ordinariate communities, to presume that the liturgical provisions flowing from Anglicanorum cœtibus should embody a simple and direct transfer of a particular form of liturgical life into the full communion of the Catholic Church. This is seen equally in the desire for the wholesale authorization of a text such as The English Missal or The Anglican Missal, as much as a view which is broadly dismissive of any distinct liturgical life for the ordinariates (or, at the least, the one that has been promulgated), either because of their use of the Ordinary Form of the Roman Rite as Anglicans (“I didn’t use Anglican texts as an Anglican, and I’m not starting now”), or a familiarity with and affection for certain modern liturgical forms of Anglican liturgy, such as the 1979 Book of Common Prayer or Common Worship. Monsignor Steenson’s point, then, which I believe most properly illustrates the intentions of Anglicanorum cœtibus III and is in harmony with the vast majority of the interpretations given in recent papers by members of the Interdicasterial Commission Anglicanæ traditiones and officials of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, reveals a different approach which, properly understood, offers an important insight into the broader themes of Anglicanorum cœtibus and, thus, the whole ordinariate project. For our considerations, we will consider how this understanding undergirds the principle by which the new liturgical texts should be received, by the clergy and lay faithful of the personal ordinariates, and also by the wider Church.

Documents and Anglican Patrimony

To begin we should consider the founding documents of the personal ordinariates, and their discussion of the notion of the Anglican liturgical patrimony. Both the apostolic constitution Anglicanorum cœtibus and the Complementary Norms speak explicitly of Anglican patrimony in a limited and undefined way, and only in the context of the formation of candidates for Holy Orders. Anglicanorum cœtibus VI, §5, for example, speaks of the possibility of a seminary programme or house of formation “[in] order to address the particular needs of seminarians of the Ordinariate and formation in Anglican patrimony.” Article 10 of the Complementary Norms speaks of two objectives for the formation of the clergy of the ordinariates: joint formation with diocesan seminarians and “formation, in full harmony with Catholic tradition, in those aspects of the Anglican patrimony that are of particular value.” The same article further provides for the implementation of the principle of Anglicanorum cœtibus VI when it speaks of the establishment of a house of formation “expressly for the purpose of transmitting Anglican patrimony.” Both places thus define the means of transmitting the Anglican patrimony, but do not explain what it is.

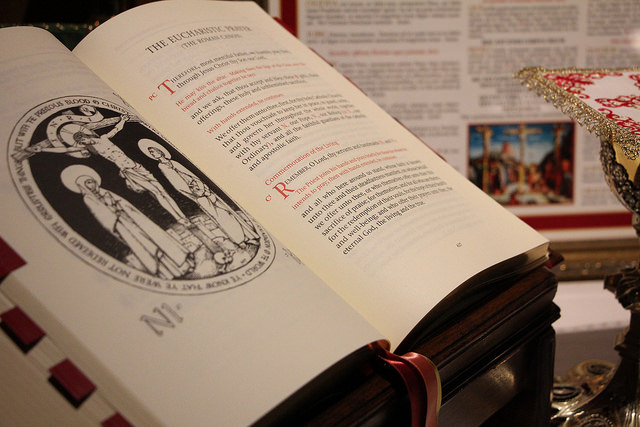

For this we must to turn to Anglicanorum cœtibus III. This paragraph states that the liturgical provision for the personal ordinariates is intended “to maintain the liturgical, spiritual and pastoral traditions of the Anglican Communion within the Catholic Church, as a precious gift nourishing the faith of the members of the Ordinariate and as a treasure to be shared.” Thus the liturgical provision for the personal ordinariates is to be understood to be dependent on the Anglican liturgical tradition, and thereby an explicit means for the transmission of the Anglican patrimony within the Catholic Church. This does not imply that the liturgical traditions of Anglicanism represent the fullness of the Anglican patrimony to be transmitted by, and maintained in, the personal ordinariates, but that these liturgical traditions, approved by the Apostolic See, are at least a constitutive element for the authentic implementation of Anglicanorum cœtibus, that is for maintaining “the liturgical, spiritual, and pastoral traditions” of Anglicanism in the Catholic Church. It is further noteworthy that the liturgical provision which will achieve this end, and which is to be considered as constitutive, is to be “approved by the Holy See” so as to maintain the integrity of the Church’s faith, and to present the Anglican tradition in a way that genuinely reveals its continuity with its Catholic origins, whilst also respecting the later context in which it developed. Thus the “submission” of the Anglican liturgical patrimony to the authority and scrutiny of the Church is an essential element of process of reunion foreseen by Anglicanorum cœtibus.

The Anglican Liturgical Patrimony

The recognition of a distinctive Anglican liturgical patrimony in Anglicanorum cœtibus is nothing new, even if the weight given it is revolutionary. A consistent recognition of the worth of the particular customs and texts of Anglican worship by the Catholic Church found its expression in the informal Malines Conversations of the 1920s, the dialogue between various archbishops of Canterbury and popes from the 1960s, the famous homily of Blessed Pope Paul VI at the canonization of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales in 1970, and consistently since then through official ecumenical dialogue. Within Anglicanism, of course, the value of a distinctive liturgical life within the wider Western tradition has been constant theme in discussion about reunion with the Apostolic See. Even at the height of Anglican Papalism, the translations of the Missale Romanum that gave expression to hopes for unity with Rome, such as The English Missal and The Anglican Missal, were themselves formed around the language and vocabulary of the Book of Common Prayer. Thus any form of reunion consistently sought to preserve something of the Anglican liturgical patrimony for those who came into the Church through any potential provision, and a gift to be shared with the whole Church. It was of course this missal tradition that ultimately led to the adoption of the post-conciliar Missale Romanum by certain parishes and clergy of the Church of England.

It was such a conviction for an Anglicanism that was “united but not absorbed”, to use a famous phrase, which in a certain sense led to the free surrender of this much-loved tradition to the Apostolic See, by those who accepted the terms of Anglicanorum cœtibus. Such an act did not seek to “give up” the Anglican patrimony but, on the contrary, betokened a necessary degree of trust on behalf of those coming into full communion with the Catholic Church, and a certain confidence in the recipient of the gift—that is the Holy See—and in particular in her authority to discern and refine, to winnow and prune. We might say that the many local and individual ingredients of Anglican liturgical life, which were presented in faith to the Church by those who availed themselves of this provision, were handed over in the sure and certain hope that she would offer in return a feast that would amply and ably nourish her newest children in the apostolic faith.

The Liturgical Life of The Personal Ordinariates

In this sharing of the gift of the Anglican liturgical tradition with the Catholic Church, those who have come into the personal ordinariates have implicitly acknowledged the rich heritage and authority which already resides within her bounds. Nothing new is ever brought to the Church, and all she requires has been given to her already by Christ. Thus the liturgical life of the personal ordinariates must express, albeit in a distinctive way, the one and ancient faith in a manner that is in complete harmony with the wider Tradition. As has been said elsewhere, it is for this twofold reason—doctrine and liturgy—that the very working group examining the liturgical provision for the personal ordinariates, drawing on those rich traditions of the Anglican liturgical patrimony, itself comprised the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. Both the liturgy qua liturgy, and the liturgy as an expression of the faith of the Church, were thus under scrutiny.

The rich deposit of the Anglican liturgical patrimony, which in its diversity is notoriously obscure to define, thus underwent something of an examination by the authority of the Church, in order to establish what of it might be retained for use in the communities of the personal ordinariates. It may be said that this process does not completely conclude with the promulgation of the liturgical books of Divine Worship, but it certainly does come to a prolonged rest as the Church’s discernment and consideration finds its place in these ritual texts. The “ingredients” of which we spoke above—the charming but sometimes confusingly diverse liturgical patrimony of Anglicanism—has been helped to bear fruit in its new context by the Church’s unique knowledge of truth, goodness, and beauty, as the Bride of Christ and his mystical Body on earth. That is to say (and this is key): there is no longer a nebulous “Anglican patrimony”, which remains undefined and unruly and which, as Monsignor Steenson opined, “can be defined by as many people that happen to be in a room at that time”, but rather something ordered aright and presented anew—fully Catholic yet truly Anglican in heritage—now available to the faithful of the personal ordinariates and, indeed, the wider Church, in the provisions of Divine Worship. The “ingredients”, we might say, have been weighed and measured into something which is altogether “new”, and yet instantly recognizable as an authentic expression both of the Roman Rite and the Anglican liturgical patrimony.

Conclusion

With this in mind we might conclude with two simple points. First, the preservation of the Anglican liturgical patrimony within the Catholic Church is definitively achieved in the texts of Divine Worship. To be sure, other means of expressing this may be found within the life of the ordinariates and, as we have said, this discernment is not over—how can it be? However, it is the liturgical books of Divine Worship that must now be considered the principal, and even essential means of transmitting the Anglican liturgical patrimony in the Catholic Church, both for the faithful of the personal ordinariates and as a treasure to be shared. This is an explicit expectation of the apostolic constitution and, as we have demonstrated, a constitutive element of the vision expressed therein.

Secondly, with the advent of Divine Worship the communities of the personal ordinariates need no longer consider their experience as Anglicans as the sole measure of their liturgical life—constantly referring back to what was done on the other side of the Tiber. Rather, whilst always keeping that rich history in mind, we now find in the promulgated books of Divine Worship the authentic expression of the juridical, ecclesiological, and spiritual life of the personal ordinariates, refined and presented anew by the Church, for the edification of all. Thus it is this “codified” Anglican patrimony, and not the subjective experience or individual expectation, upon which the merit and worth of each endeavour within the life of the personal ordinariates may now be measured.

Dear Editor,

I have concerns about some points in Fr Bradley’s piece on Divine Worship, concerns that he is in some details presenting a particular version of patrimony which may not be fruitful in the longer term.

(1) He notes that Anglican patrimony – what we have brought with us – is diverse, and local. He then suggests that this diverse and local patrimony needs to be scrutinised and validated by the Holy See, not imported tout court into the Ordinariate, mentioning particularly the modern Roman rite and the Anglican / English Missal traditions within Anglo-Catholicism.

My reply would be that as regards the modern Roman rite, this remains an option for all Ordinariate priests; and the Anglican Missal, for example, with use of the Roman canon, could have (legitimately) been imported almost unchanged within the Ordinariate. The decision not to do so was not a theological or even a liturgical one. The Anglican Missal tradition was fully and explicitly Catholic, and is in fact both more traditionally Catholic and more Anglican than the modern Roman rite, as it can point to a greater continuity with the historic Roman and Anglican liturgies.

I do not think, therefore, that the Anglican or English Missal presented a “problem” for Catholic theologians and the Holy See. The decision not to import them was one of policy, and exactly what guided that policy is open to question.

(2) Fr Bradley says that the “nebulous” and subjective ideas of local and diverse patrimony have now been replaced by a “codified” liturgy. The codification, however, was achieved precisely through subjectivity… someone chose which bits of this diversity should be kept. Liturgy is (by its nature) not a piece of paper but an Act, an Act of worship: there is a reasonable doubt as to whether liturgy should be normally legislated upon by those who do not have a long experience of its performance. Before Trent, and in the Orthodox church till now, the local ordinary was the authority over local variations. To suggest that the local and subjective should be set aside for the standardised (but still subjective) is certainly the way that liturgical authority has been increasingly exercised in the Catholic church since Trent. But this is itself a very doubtful and arguably untraditional development, and sets aside the normal authority of the ordinary.

I would not disagree that the Ordinariate liturgy – involving as it does the integrating of elements that developed outside full communion – presents a special case, and the Holy See should rightly scrutinise the theology of any proposed liturgy. But scrutinising the results is not the same as directing and limiting the process. I have heard, for example, that the possibility of an Anglican Eucharistic prayer was ruled out from the outset by the Holy See (whether a revised form of one of the “catholic” Prayer Book revisions or whatever), irrespective of its theology… and also that the possibility of a modern language rite alongside the traditional language of Divine Missal was explicitly ruled out. These seem to me to be cases where Holy See continued its policy of making decisions on liturgy that belong properly to the local ordinary, and I think that this ought to be raised as (at the very least) questionable. Fr Bradley seems to assume that the current ideas of proper “submission” to the Holy See are unproblematic in how they are exercised at present.

(3) Finally, Fr Bradley suggests that, rather than looking back to Anglicanism for liturgical patrimony, we now have Divine Worship as a “definitive” reference point. But given the concerns highlighted above (the absence of a revised Anglican Eucharistic prayer, for example, and the use of the Novus Ordo lectionary instead of the annual traditional English Missal KJV lectionary), one should question this assumption. There are elements of the Anglican liturgical tradition most certainly consonant with Catholicism that are not catered for in Divine Worship, however grateful we are for it. If Divine Worship becomes the reference point, if we do not cultivate our knowledge for and love of other catholic Anglican traditions that have not been included – and perhaps in the future request their inclusion – I do not think we are preserving patrimony but rather a particular subjective codified version of it. The point is not to look back (over our shoulder) to the Anglican church that we have just left, but to the richness of an Anglican liturgical tradition which should exert an influence on future liturgical revision in the Ordinariate; in the second sense, we ought to be looking back.

I should finish with two disclaimers, the first being that I am not attacking Divine Worship as inadequate, but wish to point out that it is (inevitably) incomplete as patrimony, and (inevitably) has not had an utterly perfect process of composition. And we should not pretend that it is either complete or perfect. Fr Bradley may not disagree with all of the points I have made above, and there are caveats within his text which do (partly) meet my objections. But I believe that, given his overall thrust, my concerns about some details of his presentation are justified.

Yours faithfully.

Thank you, Timothy, for being the first to implement our new Comments Policy